Not Worth the Blood

Adventures on the Southern Border

“Except for its geographical position, New Mexico is not worth a quarter of the blood and treasure expended in its conquest.” - Brigadier General William H. Emory

“Mama, why is this here?” my daughter asked as we drove slowly alongside the dizzying, massive structure. “I mean besides racism?”

Well shoot, honey. Besides racism? It’s hard to know how to find a thread to start talking about the border without bringing up racism. It’s not like the grass is greener north of the border. Desolation feels like the most useful adjective for describing the landscape, towns, and people in this part of America. I guess the “why” starts with the fact that Americans really wanted the gold in California, and New Mexico was totally in the way.

It must have been a crazy time, back in the middle of the 19th century. In America, it was all about manifest destiny! Expanding the Republic from sea to shining sea! In Mexico, it was about revolution! and more revolution! and more revolution! and more revolution. Que viva!! In 1820, the US and Spain had been close to signing a treaty to formally establish a boundary, which would have ceded what is now California, Nevada, Utah, Arizona, New Mexico and Texas, along with about half of Colorado, bits of Kansas and Oklahoma. Before any treaty could be finalized, Mexico broke from Spain.

New Mexicans were royalists to the bone, in no small part because the Spanish crown supported the mission project, providing a fairly dependable trickle of income and goods to the impoverished colony. New Mexico’s last Spanish Governor, Don Pedro Pino, had pleaded with the crown for protection against the aggressively restless Americans. Subsequent governors would plead with whichever Mexican government was in power during those turbulent years, but no help was ever provided, and not only did the restless Americans pour in on the Old Santa Fe Trail, but a few years later they invaded on that very trail, as always, en route to somewhere more interesting (in this case, Ciudad Chihuahua).

By the time the dust settled and the ink dried on the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo, America discovered it was stuck with New Mexico. And if that wasn’t enough, a few years later, they had to buy a little more to tack on at the bottom so the Southern Pacific trains could go through. The government gifted quite a bit of land to the railroad companies, and the Southern Pacific tried their darnedest to sell the heck out of the Chihuahuan desert scrublands, walking right up to the line of outright fraud, with the hyperbole they published in their organ, Sunset Magazine. “Everlasting and inexhaustible” water? Psssht, not EVEN!

The job of surveying the border first fell to the one John Bartlett, who spent a lot of time partying and dancing and admiring the low-cut necklines popular in New Mexico at that time. He accidentally ceded quite a bit of land to Mexico through his cavalier carelessness, but the Gadsden Purchase resolved the error. The job of TRULY establishing the border then became the work of Brigadier General William H. Emory, who took his job incredibly seriously. Emory wrote of his expedition:

My own expectations, and I hope those of the government, were entirely fulfilled in the manner in which the work was accomplished. Under all circumstances-- during the cold winter exposed upon the bare ground of the bleak plains, and in the summer to the hot sun blazing over the arid desert-- every order was executed with fidelity, and the work was completed within the time, and largely within the amount appropriated by Congress.

We passed the entire width of the continent and returned with the loss only of two men, and without losing a single animal, (except those worn out by service), or suffering a stampede by the Indians ; at the same time that our co-operators on the Mexican commission were twice robbed of every hoof by the Apaches, and extensive losses were sustained by other detachments of United States troops, and by our citizens traversing this region.

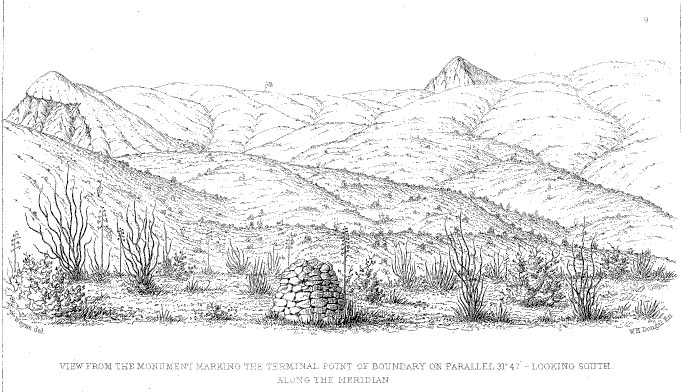

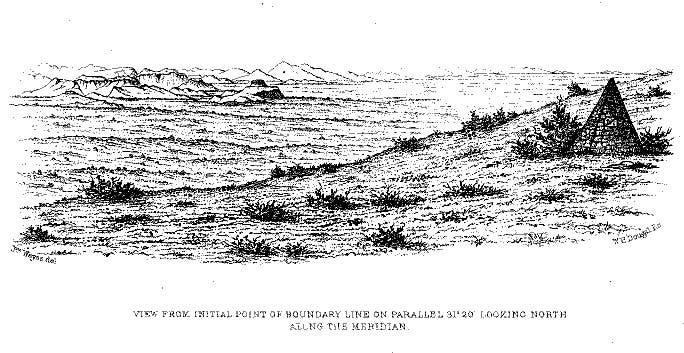

Starting at El Paso, and throughout the desert, Emory built stone monuments to mark the border. We had traveled down there to find this one, right on the corner of the bootheel.

Sadly, the whole border is so obstructed now that getting to the monument— which is still there because the terrain is so rugged the fence has gaps— did not seem possible in the vehicle we had, or in the time we had. It’s worth it to note that everything looks pretty much exactly like it did in Emory’s time. This is some incredibly hostile land, filled with a variety of plants with long thorns, and also venomous snakes. As Emory pointed out, this hostile land was already inhabited, even before the Spanish, by the famously hostile Chiricahua Apache.

The Spanish, and then the Mexicans, coped with the Apache as best as they could, but the Americans were determined that nothing was going to stop economic development in this particular desolate patch of land, so they sent the US Army to deal with it. Except because this was happening after the Civil War, they sent the newly-created colored battalions, who eventually became known as “Buffalo Soldiers” down to the border to fight all the people in the land they inadvertently seized.

A doctor who spent years stationed with these battalions wrote,

“to the west and southwest stretched the limitless prairie, dreary and desolated. The only green things visible in the landscape were the few stunted trees at the spring, half way between the Fort and the entrance to Cook’s Cañon. After marching for days and weeks through an enemy’s country, with the rough mess-kit of a campaigner, with the horror of a visitation of cholera, to which their brave surgeon and his wife fell victims, these ignorant colored soldiers who had been buoyed with delusive hopes on leaving the fertile lands of Georgia, found themselves in this dreary, prison-like abode, exposed to all the discomforts of a home in the desert, and to all the dangers of a powerful tribe of merciless Apaches, forever on the warpath.”

Even after things got settled with the Apaches, the Army continued to deploy the Buffalo Soldiers to protect corporate infrastructure in desolate places, including mines and railroads.

One of the most unpleasant outposts must have been Camp Furlong, just north of the Mexican border, protecting the Southern Pacific railroad depot, hotel and customs office. When I first came across these pictures at the UNM library, I thought they were taken outside the camp. They were not, they were taken in camp. This was where these men had been living for four years. In tents. When I stood in this place recently, it was bitterly cold, windy, and alternating hail, rain and snow. New Mexico State Parks has planted cactus all over so it looks quite pretty, but just beyond the town, it’s back to the mesquite and creosote and dust devils. If you look at this picture, they’re all sitting on ammo crates, because that’s all they got from the Army. How do you tell this story without racism?

So that was how things stood at the turn of the 20th century. America had more or less fought itself out…. but Mexico had not!

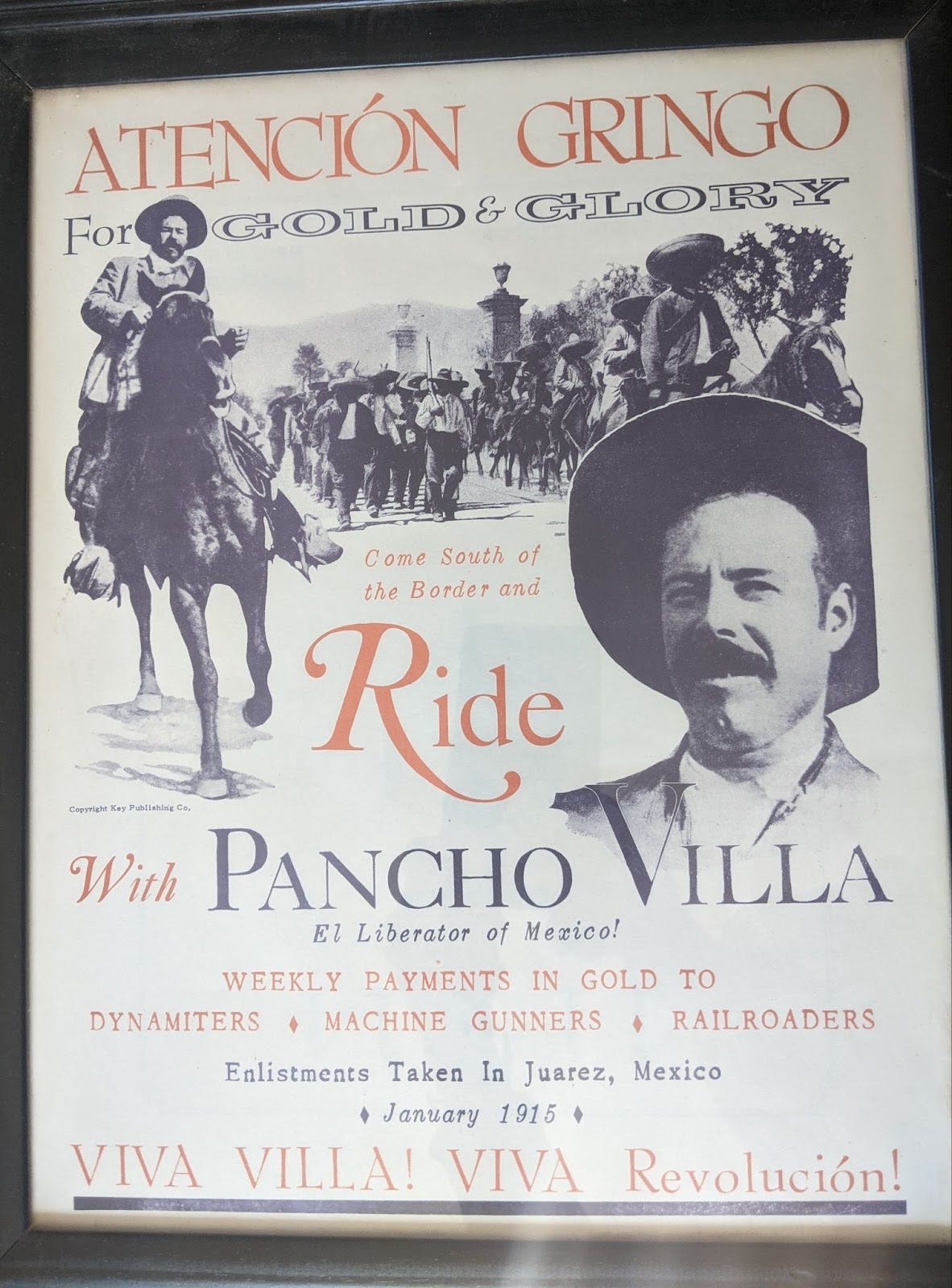

I’m told that Pancho Villa was the first reality star, and was sort of just having a revolución for the hell of it, and staging stunts for the press like issuing his own currency or invading America. So he crossed the border with his troops, and scuffled with the Buffalo Soldiers (who had to bust the lock off the armory because the white COs had locked up the ammo and lost the keys), then retreated.

In this part of the world it was the greatest thing that ever happened! The soldiers at Camp Furlong got buildings to live in! Columbus got on the map! Nowadays you can visit Pancho Villa State Park and if you’re lucky, eat at Pancho Villa Burritos food truck. We were not lucky because as I said, it’s desolate, and Columbus is quietly dying in the sun. Its primary purpose seems to be hosting people getting dental work done five miles away in Puerto Palomas de Villa, where a magnificently heroic Pancho Villa greets you as you cross into the country.

Puerto Palomas is everything Columbus is not. It’s lively, full of children and young people, with abundant restaurants and shopping. The medical industry dominates the town, with large, modern dental and vision clinics serving the desperate Americans pouring across the border. But nearly everywhere you go in town the border wall dominates the landscape, looming over residents’ bungalows and gardens.

This specific bit of fencing seems to have been a particularly expensive artifact of George W. Bush’s Global War on Terror. His newly-formed, sinister Department of Homeland Security pushed for the Secure Fence Act of 2006, which ended up costing over six billion dollars and broke numerous environmental laws to build several hundred miles of border fence. The hysteria of the GWOT fueled hysteria around immigration, and an early version of MAGA involved the border ranchers forming a militia to drive around in jeeps and shoot at migrants and destroy water caches. Under pressure from the right, Obama continued to fund the work, adding cameras and other technology to monitor border crossings, and CBP completed the fence in 2015, including many miles of pedestrian fencing, secondary fencing and tertiary fencing.

Customs and Border Patrol seems like they’re probably the highest paying jobs down in the bootheel, and pretty sweet gigs, too. In our effort to find the corner monument, we saw CPB guys in their trucks with the big police cameras on them, in their trucks watching traffic, and in their trucks at the checkpoints. They did not get out to interact with us. The 5G is not great out there but maybe they have porn downloaded on their laptops. It’s pretty lonely otherwise. The train doesn’t even go through any more; the embankments are collapsed and the tracks have been pulled up.

So…. why is that terrible, brutal scar of a wall here? Besides racism? Greed, to start with. A sense of exceptionalism. Theater and ego. A reckless disregard for the land and its people in favor of scoring political points. Coastal scorn for the heartland.

And it really wasn't worth it.

Great story and history.