Remembering New Mexico's Buffalo Soldiers

Commemorating Soldiers and Citizens

After the Civil War ended, the United States turned its energies into warring on the Native people, or as military documents put it, “securing the western frontiers.” In New Mexico, raids on settlers had increased while the Anglos fought each other, and the U.S. Army was willing to back an ambitious, but ill-conceived plan to remove some of the Natives from their homelands and turn them into peaceful farmers. Toward this effort, the Diné were driven from their homes, and forced to march to Hwéeldi, the place of suffering and fear, where they were held with many Mescalero Apaches. In 1868, the Diné negotiated a treaty enabling them to peaceably return to their sacred homeland. The full might of the military then turned against the Chiricahua, Mimbres and Mescalero Apache for another two decades.

Life was daily misery, privation, and danger for soldiers stationed out in New Mexico. Memoirist James Bennett’s commander was killed by Apaches in the White Mountains, and although barefoot in February, Bennett survived the icy mountains on a “light diet” of horse and mule flesh to return Captain Stanton’s remains to his widow. Malaria turned out to be a surprisingly bad problem for the riverside forts; Fort Thorn was entirely decommissioned because of epidemic conditions.

The military’s solution to the horrible conditions was to send in newly commissioned Black soldiers (later nicknamed Buffalo Soldiers), many newly freed and wishing to leave the south. The 57th and 125th Infantry Regiments arrived in 1866 and were stationed between Fort Stanton and Fort Selden.

Nothing about their service was easy, starting with the resentment of the white soldiers. The military doctor W. Thornton Parker wrote about when the first detachment of Black soldiers was sent to Fort Craig for guard duty. The white soldiers there were “bordering on munity” and “bloodshed was seriously anticipated.” The white soldiers refused to present arms or acknowledge the new guard despite direct orders, so the officers hung them by their thumbs until they agreed to “salute the uniform of the United States” regardless of who was wearing it.

The Black infantrymen often got the most menial or dangerous jobs. Most jobs at some forts, like gathering firewood, were both. Fear of encountering the Apaches was constant, so soldiers could not leave their garrison without permission, and usually hunted in large parties.

Describing the troops’ life at Fort Cummings in 1867, Parker wrote

“to the west and southwest stretched the limitless prairie, dreary and desolated. The only green things visible in the landscape were the few stunted trees at the spring, half way between the Fort and the entrance to Cook’s Cañon. After marching for days and weeks through an enemy’s country, with the rough mess-kit of a campaigner, with the horror of a visitation of cholera, to which their brave surgeon and his wife fell victims, these ignorant colored soldiers, who had been buoyed with delusive hopes on leaving the fertile fields of Georgia, found themselves in this dreary, prison-like abode, exposed to all the discomforts of a home in the desert, and to all the dangers of a powerful tribe of merciless Apaches, forever on the warpath.”

On top of that, “Every possible punishment employed in the discipline of frontier posts was inflicted on them.”

Despite the hardships of these posts, and the discouraging beginnings, the Black troops distinguished themselves as “trustworthy, brave and intelligent,” particularly the 24th and 25th Infantry and the 9th and 10th Cavalry. The fabled 9th Cavalry relocated their regimental headquarters to Fort Union between 1875-1881, and from there deployed to Fort Bayard, Fort Craig, Fort Cummings, Fort McRae, Fort Selden, Fort Stanton, Fort Tularosa and Fort Wingate. The 9th Cavalry not only fought bravely against the Apaches in “Victorio’s War,” but helped restore peace during the violent upheavals in Lincoln and Colfax counties.

Geronimo’s band of Chiricahua Apache surrendered in 1886, and the United States slowly decommissioned their forts, allowing some to crumble into the ground, and repurposing others as hospitals. The final active Black regiments, members of the 25th Infantry Regiment and ninth Cavalry Regiment, were stationed at Fort Bayard and Fort Wingate 1898-1899. After leaving the military, many men established homesteads, particularly in eastern and southern New Mexico.

Earlier this year, I was honored to assist with a commemoration project to honor some of these men. In an unlikely but fruitful alliance, the New Mexico Buffalo Soldiers Motorcycle Club and the Lew Wallace chapter of the Daughters of the American Revolution teamed up to create audio eulogies for each Buffalo Soldier buried in historic Fairview Cemetery in Albuquerque (that the DAR ladies could find records for), starting with the first newly freed men like James Price.

Sargeant James Price

From my amazing colleagues at the Salus Populi Pension Project, I was aware that the the records of colored soldiers were not well maintained or preserved. However, I was unprepared for how scant the documents turned out to be. In many cases, we had an enlistment date, a re-enlistment date, and a date for mustering out. In some cases, there was paperwork for a charitable group paying for a funeral or headstone.

Private Oscar Warner

In order to paint a clear picture, we created timelines for where these troops had been stationed. It became clear that well after the territorial era, these Buffalo Soldiers stayed in the thick of things, from combating Pancho Villa down at Camp Furlong to fighting alongside Teddy Roosevelt in Puerto Rico and the Philippines.

Private Sammuel Scott

On retirement, many of the veterans in Fairview got jobs with the railroad and settled in downtown Albuquerque. There, they continued to support each other, trying to negotiate a system that delayed both health care and benefits long past death, like in the case of poor Joseph Cammel.

Private Joseph Cammel

The pictures that emerged were heartbreaking, maddening, and incredibly inspiring. Despite everything in the system being against them, these men served honorably, lived honorably, and contributed to a diverse and vibrant community where their descendents could thrive. Eleazar Reynolds did not let his illiteracy stop his rise in the military ranks, but he ensured his children could read and write.

Sargeant Eleazar Reynolds

This project cost little beyond time and love to put together and it’s a beautiful way to surface heros (on many levels) who would otherwise be erased and forgotten. We’re hoping to work next with Fort Bayard in Silver City, the final resting place for many more of these valiant frontiersmen.

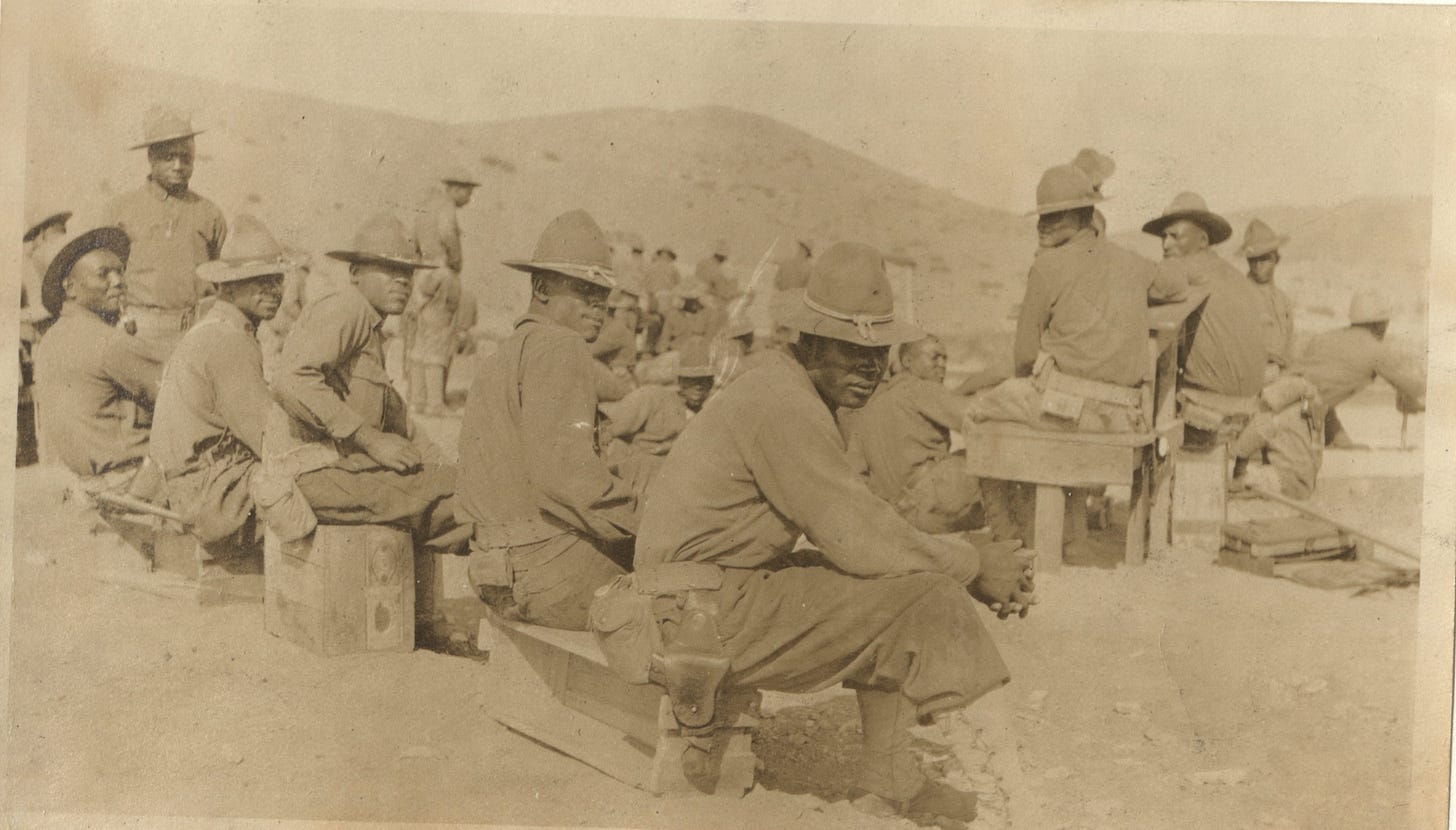

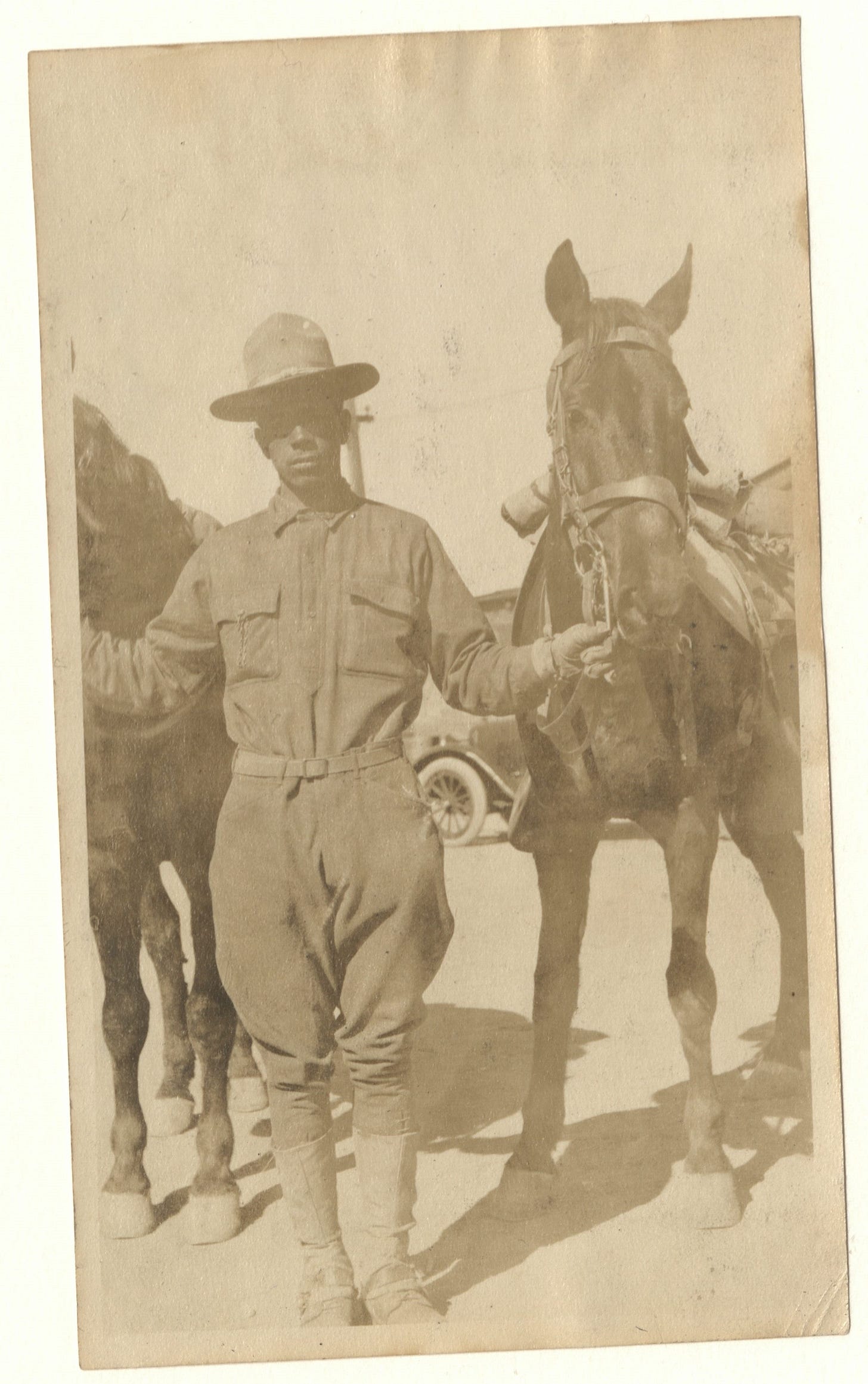

photographs of African American soldiers; Columbus (N.M.); 24th Infantry Division; 1918. Courtesy Center for Southwest Research, University Libraries, University of New Mexico

Wishing everyone a meaningful rememberance and the hope of peace.

Wow what a wonderful piece. The photos are gorgeous. To pause and consider the profundity of the journey from their formerly enslaved ancestors (in their familes' very near past at that time) risking everything to gain freedom and autonomy, against all odds and amid acts of cruelty and ignorance all around. Wow. What an arc. The multitude of acts of deep disrespect they had to endure daily and even after death.

It stands to be noted that while fighting bravely against the Apache they were still fulfilling the horrific genocidal agenda of their colonialist bosses. It's very problematic! And complex. All Americans need to wademintonthe history of the west with clear eyes. What else were they supposed to do, defy orders and be gleefully murdered by white troops just looking for a crack in the armor of the troops of color? Stay in the South while the KKK was riding?

I prefer to say "people/soldiers of color" rather than "colored people/soldiers" whenever possible. Micro-anti-hate speech I guess. Seems like a much finer and more empowering brush to use. It's a small point but kind of stuck out to me in the language.

Anyway, it's a treasure to read this important and challenging account, beautiful job, and how lucky for me that I got to enjoy it on this misty morning. Thank you.